Sturtevant

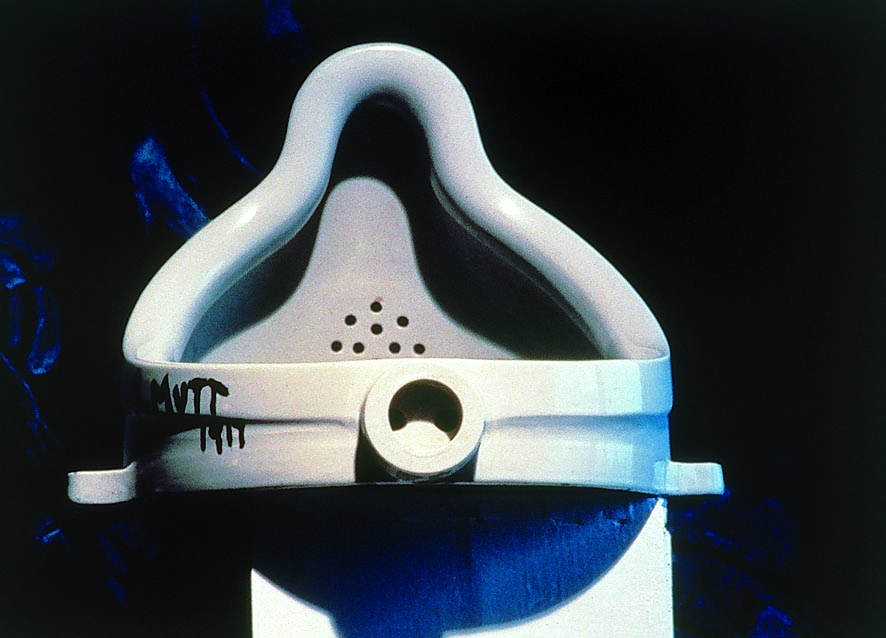

The art of the present has always made the art of the past look different. These days, the late twentieth century has stirred up endless reshufflings and disclosures about how what used to look bad can suddenly look good (as in the new enthusiasm for the later work of Picasso, de Chirico, or Picabia), or about how individual artists who once appeared peripheral and singular may now seem voices in the wilderness, announcing artistic events to come. I can think of no more startling example of the phenomenon of a newly discovered prophet than the case of Elaine Sturtevant.Between 1965 and 1975, during which time she had nine solo shows and participated in nearly a dozen group shows, she raised a storm of controversy by re-creating exactly, down to their very dimensions, paintings and objects by not only Duchamp, that old master of confounding original and reproduction, but also, still more bewilderingly, a roster of her contemporaries - Johns, Stella, Warhol, Lichtenstein, Rosenquist, Oldenburg, Beuys. For some her work was outrageous plagiarism. But for others her role in the art world was distinctly disturbing, far more than an abstruse meditation on questions of artistic originality.

And then, oddly enough, came the 1980s, when our retrospective century, possibly readying itself for the Last Judgment of the year 2000, suddenly produced a crop of artists who were passionately preoccupied with the resurrection and embalming of the ever more widely disseminated images in the Hall of Twentieth-Century Fame. Under the verbal banners of "appropriation", "simulationism", or "image-scavenging", such painters as Sherrie Levine, Philip Taaffe, Mike Bidlo, and David Salle have copied everything from Schiele, Malevich, and Picasso to Newman, Riopelle, and Pollock. This new visual world of double-takes has not only raised a lot of unsettling questions but has also moved Sturtevant's work far closer to the centre of the history of art in the last quarter century.Now that we have a wider range of experience of artists who replicate other artists' work, what makes Sturtevant's art her own and nobody else's (apart from its clear historical priority) continues to nag us. Part of her audacity is doing works by her immediate contemporaries rather than by remote and venerable father figures. Part of her clarity, which complicates things further, lies in proclaiming that these works belong to her aesthetic domain alone.On a more complex level, she opens the Pandora's box of the meaning and viability of originality; and mirroring the preoccupations of Duchamp, she raises the spectres of truth versus falsehood, conception versus execution, and other mind-bending issues. Her own fiercely absolute consistency makes her, paradoxically, infinitely more original than an infinity of willfully original artists.Her preoccupation with original versus double turns out to be amazingly in tune with life as we know it at the very end of our century. She makes us look backwards as well as sideways and forwards, and there we see, not surprisingly, copy, double, imitation, image, simulacra and resemblance reigning supreme, pushed to the very top by cybernetics and its cyber fold.Not the least of Sturtevant's unsettling powers is to trouble the future of art as well as its past and present.During the opening of the exhibition Sturtevant a special Drawing Competition is organised. The awards are given by the "Marx Brothers" on Friday 16 July 1999.